The surprising strength of self-compassion

The science of being on your own side.

Self-compassion can seem counterintuitive. For some people, the idea of being kind to yourself feels self-indulgent or a bit fluffy - not the sort of response that helps you perform under pressure.

And yet, the evidence points in the opposite direction: self-compassion often helps us stay steadier, more resilient and more effective when things are hard.

When coaching, I often hear clients say that being tough on themselves helps them to excel. It pushes them to strive for more and ensures they don’t drop the ball. Many people take pride in being their own harshest critic.

They replay mistakes, go over every detail and use self-blame as motivation not to repeat them. Beneath that is an understandable fear that easing up might lead to complacency - a slippery slope towards falling standards, missed expectations or, worse still, reputational damage.

But while self-criticism can keep us humble and alert to our shortcomings, it often comes at a cost. It can fuel self-doubt, low mood and anxiety, and increase rumination and avoidance, making us more likely to procrastinate.

Imagine speaking to a child in the same way many of us speak to ourselves. It’s easy to see how quickly that would undermine their confidence, self-esteem and willingness to try. The same dynamic plays out internally: constant criticism triggers threat and pressure, making it harder to think clearly or perform consistently.

The benefits of self-compassion

In contrast, evidence suggests that self-compassion - responding to difficulty with understanding and support - is linked to a wide range of benefits.

Meta-analytic findings show a relationship with improved psychological wellbeing, and other research associates higher self-compassion with fewer physical health complaints. In practical terms, people who are more self-compassionate tend to report:

- Lower anxiety, depression and burnout

- Less rumination and fear of failure

- Greater optimism and life satisfaction

- Faster recovery from setbacks

One reason may be that being kinder to ourselves can dampen the stress response, reducing the physiological strain - including inflammation - associated with chronic mental distress. People higher in self-compassion are also more likely to protect helpful habits like good sleep, a balanced diet and regular exercise, which support both wellbeing and performance.

Kristin Neff, a pioneer in the study of self-compassion, puts it simply:

The research is really overwhelming at this point, showing that when life gets tough, you want to be self-compassionate. It’s going to make you stronger.

What does self-compassion look like?

Neff describes self-compassion as involving three key elements:

- Self-kindness rather than harsh judgement when you make mistakes or fall short

- Common humanity: recognising that struggle and imperfection are part of being human

- Mindfulness: allowing difficult feelings to be present without being swept away by them

This last point matters more than people often realise. Self-compassion isn’t about forcing positivity or pretending things are fine. It’s about being able to say ‘this is hard’, without turning that into ‘and therefore I’m failing’.

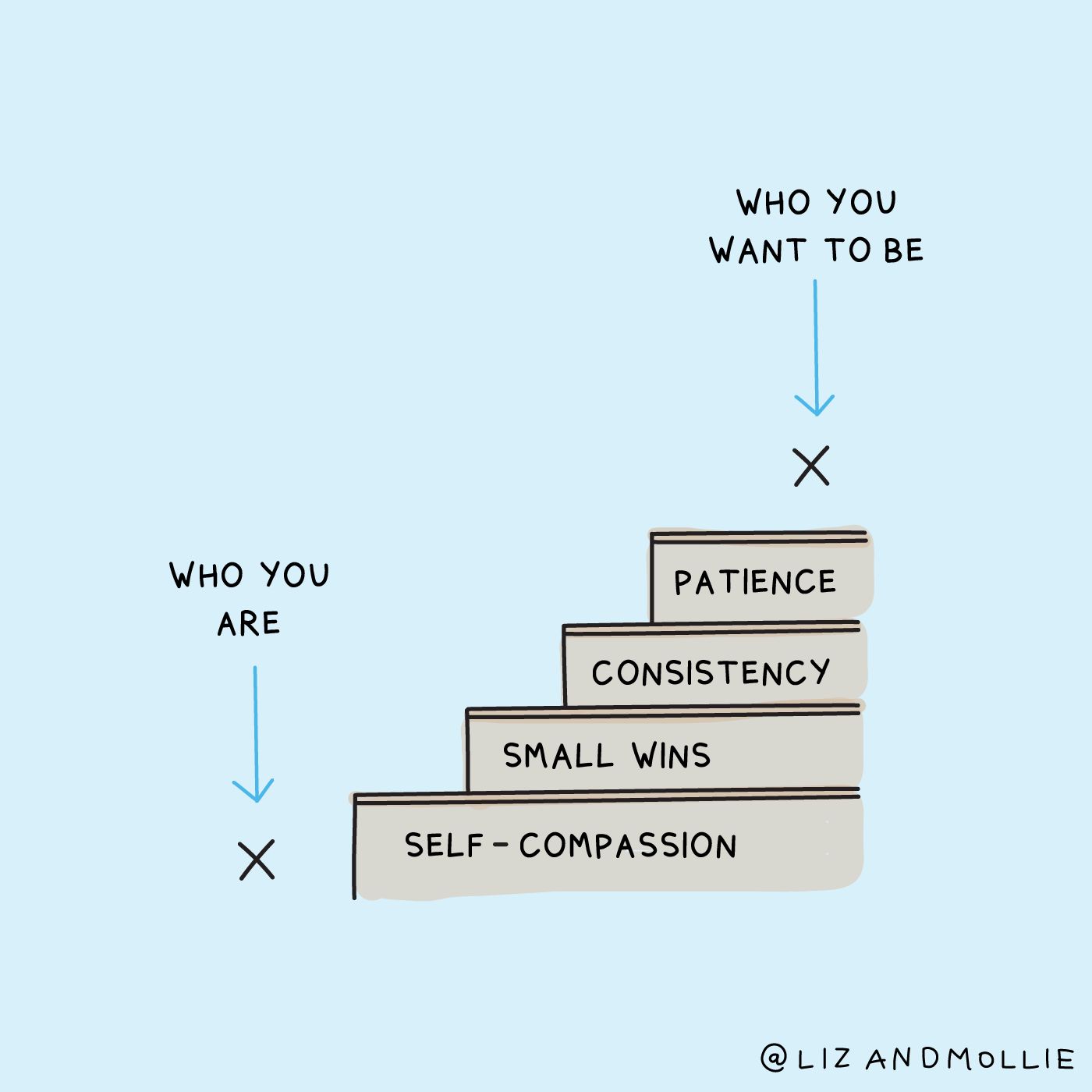

For some people, these practices come more naturally than for others. Our personality, environment and life experiences shape how self-critical we tend to be and what we’ve learned to expect from ourselves. But the good news is that self-compassion can be cultivated. And, like any skill, it strengthens over time.

How can you cultivate self-compassion?

Changing ingrained thinking patterns takes time, so patience matters. Rather than forcing change, the aim is to build more flexible, supportive responses in moments that would normally trigger self-criticism.

Here are a few ways to start:

- Pay attention to how you speak to yourself. What themes show up? How often does your inner dialogue revolve around ‘shoulds’ or rigid expectations? What tone does it carry and whose voice does it resemble?

- Notice self-criticism without turning that awareness into another judgement. The goal isn’t ‘I must stop being self-critical.’ It’s simply noticing: ‘there it is again’. That small moment of awareness creates space to choose how to respond.

- After a setback, ask what you would say to a friend. Self-compassion doesn’t mean ignoring mistakes. It means responding in a way that’s objective, constructive and focused on what you can do next.

- Practise in lower-pressure moments first. Start by being gentler with yourself in lower stakes situations so you can build the capability for more challenging ones.

Self-compassion also shows up in everyday behaviours — taking breaks, eating lunch, switching off in the evenings, and allowing time to learn rather than expecting to master things instantly.

It includes asking for help when needed and holding expectations that stretch you without tipping into self-punishment. Over time, these small actions create space for healthier, more sustainable motivation.

And if the term self-compassion still doesn’t resonate, it can help to think of it as being fair to yourself, or simply accepting that you’re human. The author Oliver Burkeman describes it as the reverse Golden Rule: rather than treating others as you’d like to be treated, don’t treat yourself worse than you would treat other people.

If you would like to chat about how to increase your resilience and wellbeing at work, visit my website for more information or get in touch at [email protected]